The Junk Drawer Project

We found the moment of Storage and discard particularly potent in the life cycle of electronic objects precisely because it fails to fit into one categorization.

Individuals consider electronic objects in a multitude of ways – from undesirable trash to a “milestone” and “meaningful keepsake.”

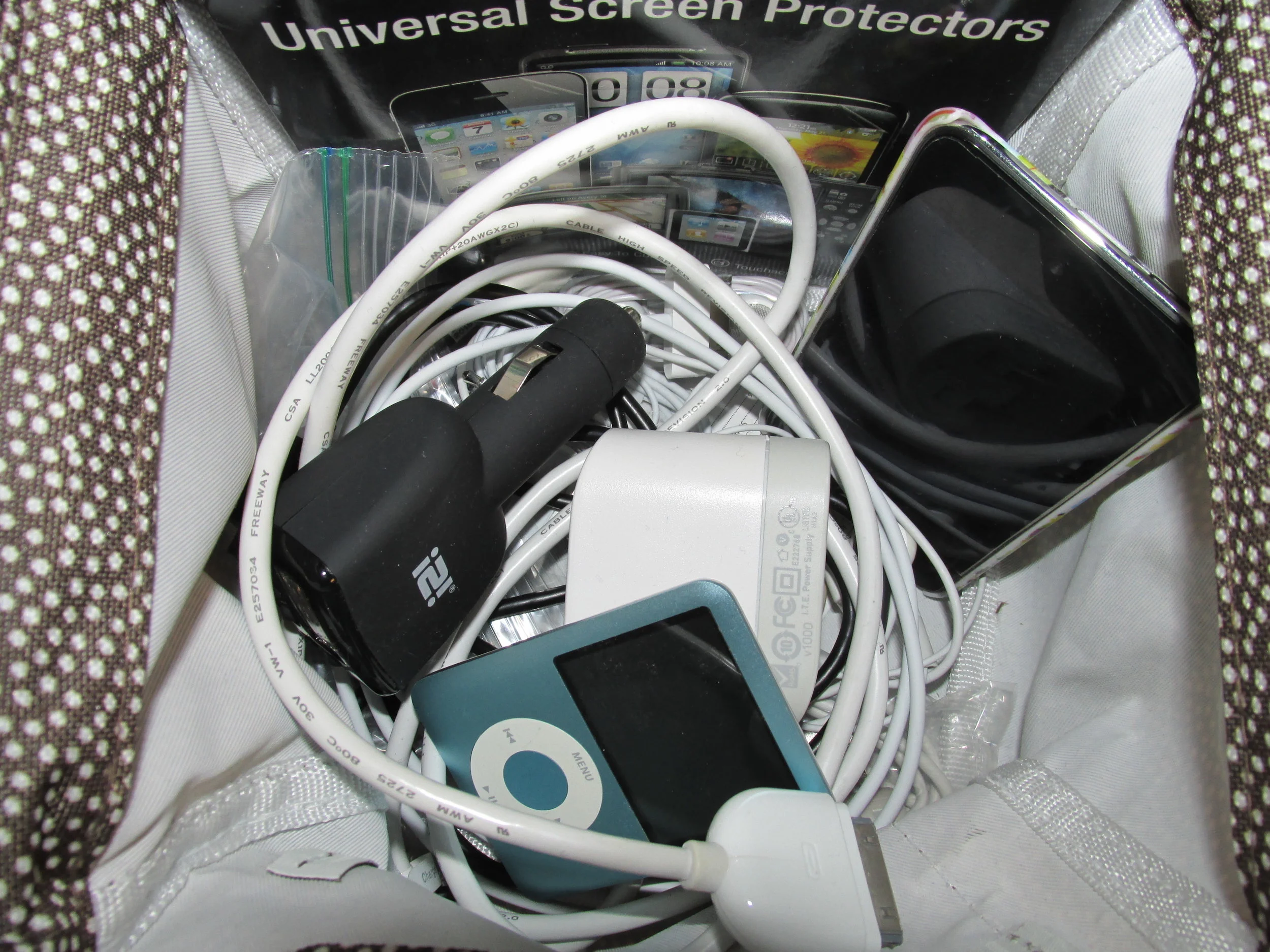

In this project, we take these reflections as incidences of a larger phenomenon, which we label the “junk drawer” at the household level.

The junk drawer represents a very particular phenomenon of household material culture where electronics are part of larger collections which hover at the stage between storage and discard. Through this lens we also seek to understand the ways in which stored electronics are influencing not only socio-environmental conditions, but the ways in which we relate to each other and more than human worlds.

The Junk Drawer Project brings together objects, images and narratives, exploring forms of value and categorical distinctions in the context of electronic life histories and e-waste formation. It emerged early on as a key part of meeting our methodological, theoretical, pedagogical, and public engagement goals. The term “junk drawer” quickly conjures a phenomenon common to many households; it also functions as a metaphor for those unintended collections of things otherwise out of place that are symptomatic of a consumer society.

The familiarity of junk drawers, which we have found often contain electronic devices, can act as an effective springboard for reflecting on the life histories of electronics and the less familiar concept of e-waste. We used the Junk Drawer Project to learn about what consumers know about e-waste generally, and to examine the concept of ‘waste’ as it applies to unused electronics stored in homes.

Junk drawers of electronic devices, bits, bytes and peripherals are situationally valued through a constellation of factors that include emotional attachments, technological obsolescence, imagined use-value, as well as discrepancies between perceived value and market value. While the problem of closet fill has been discussed by scholars, how electronics enter this interstitial stage, why they remain and what motivates movement out of this part of the life history of objects have not been closely examined. We suggest a life history approach can make these interstitial phases visible in a way that illuminates the shifting judgments of value affect the scale of e-waste distribution, speed and timing of circulation.